{{rh_onboarding_line}}

🌀 The Decode

You sit at your desk in an open-plan office. No walls. No doors. Just rows of desks stretching across a floor the size of a football field. Your screen faces outward. Your back faces a hallway where colleagues and managers walk past.

You're not doing anything wrong. But somehow, you feel like you are.

That low-grade anxiety isn't a bug of modern office design. It's a feature, one that traces back to a prison blueprint from 1791. The same logic that was built to discipline criminals now shapes how millions of us work every day.

You don’t have to face debt alone.

Debt in America is at an all-time high, but there are more ways than ever to take control.

Whether you’re managing credit cards, personal loans, or medical bills, the right plan can help you lower payments and simplify your finances.

Money.com reviewed the nation’s top relief programs to help you compare trusted options and choose what fits your life.

You can start taking back control in only takes a few minutes.

🏺 Field Notes

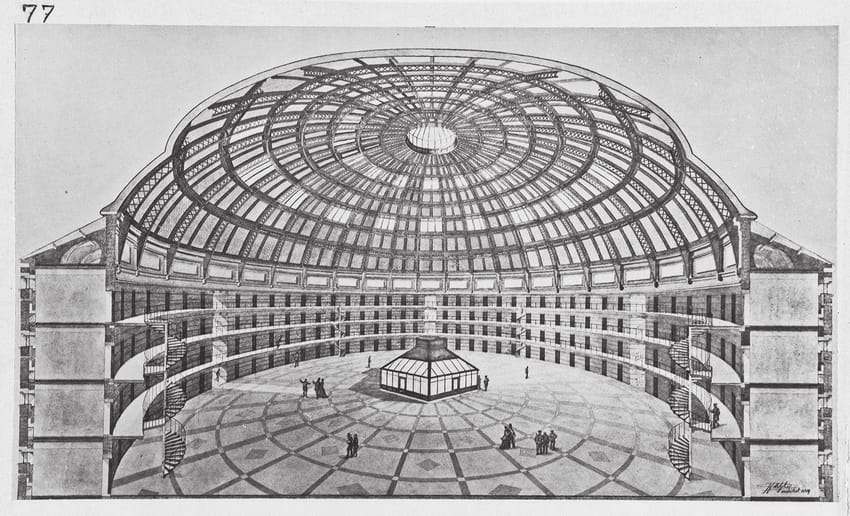

In 1785, the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham designed a building he called the Panopticon, from the Greek for "all-seeing." It was intended for prisons: a circular structure with cells along the perimeter and a central tower. Guards could see into every cell. But the cells couldn't see into the tower.

The genius and cruelty were psychological. Prisoners never knew when they were being watched. So they had to act as if they were being watched all the time. Discipline became automatic. The architecture did the work.

The Koepelgevangenis in Arnhem, the Netherlands, is an example of a panopticon-style prison illustrating principles of surveillance-based control. Adapted from Martinez-Millana and Cánovas Alcaraz (2022); figure uploaded by Sanaz Talaifar.

Nearly two centuries later, the French philosopher Michel Foucault recognized something unsettling: this wasn't just about prisons. Schools, hospitals, factories, and offices all borrowed the same logic.

The Panopticon was never widely built as a prison. But its principle spread everywhere.

🧩 First Principles

The anthropologist Edward T. Hall spent his career studying what he called "proxemics" that is the hidden rules of space. In his 1966 book The Hidden Dimension, he argued that space isn't neutral. It communicates. It organizes power.

Hall identified four zones of personal distance: intimate (0–18 inches), personal (1.5–4 feet), social (4–10 feet), and public (10+ feet). When those boundaries collapse, we don't collaborate more freely. We retreat.

This explains a counterintuitive aspect of open offices. Removing walls doesn't just remove barriers to communication, but it also eliminates the safety that makes honest communication possible. When everyone can overhear, people stop saying what they actually think. They send emails instead.

Foucault would recognize this instantly. The open office doesn't eliminate hierarchy. It internalizes it. You become your own overseer, editing yourself before anyone else has to.

What do Tom Brady, Alex Hormozi, and Jay Shetty all have in common?

They all have newsletters.

If you’re building a personal brand, social can only take you so far. Algorithms glitch. Reach tanks. But a newsletter gives you real ownership and revenue.

That’s why we built a free 5-day email course that shows you how to grow and monetize with sponsorships, digital products, and B2B services.

Usually we charge $97, but for the next 24 hours it’s free. Sign up for the course today.

🏙️ The Agora

The open office wasn't always about surveillance. In the 1950s, German consultants Eberhard and Wolfgang Schnelle developed Bürolandschaft, the "office landscape" as a reaction against Nazi-era rigidity. Their organic layouts used plants as dividers and placed managers among workers. It was intended to be democratic and egalitarian.

But when American companies imported the concept, they stripped out the humanity and kept the density. Herman Miller's "Action Office" became the cubicle farm. The cubicle farm was converted into an open floor.

The results speak for themselves. A 2018 Harvard study tracked employees before and after companies eliminated walls. Face-to-face interaction dropped by 70%. Email increased by 56%. Productivity, according to internal company reviews, declined.

Meanwhile, surveillance has gone digital. 78% of companies now use employee monitoring software, including keystroke tracking, screenshots, and mouse movements. The market for such tools is projected to reach $1.5 billion by 2032. We've traded the central tower for the always-on webcam.

And just like in Bentham's design, we've internalized it. 49% of monitored workers now pretend to be online while doing non-work activities. We perform productivity for an audience we can't see.

⚡ Signals

📜 Quote: "Visibility is a trap." — Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish (1975)

📊 Study: A 2021 systematic review comparing open-plan and private offices found open layouts were associated with negative outcomes on nearly every measure: health, satisfaction, productivity, and social relationships.

🎨 Artifact: The "mouse jiggler" is a small device that moves your cursor to keep your Slack status green. It's the modern equivalent of looking busy when the boss walks by.

😂 Meme: "Open floor plans foster collaboration,” says the company whose employees now Slack each other from three feet away.

🤔 Prompt: When was the last time you said something at work you wouldn't have said if you thought someone was listening?

📝 Reader's Agora

We’re curious about your workspace archaeology. What does your office layout say about what your company actually values versus what they claim to value? Reply and describe what your desk reveals about power in your workplace.

🎯 Closing Note

The Panopticon was designed to induce self-discipline among prisoners. Open offices and monitoring software function similarly. The architecture does the watching, even when no one's in the tower.

But there's a crack in the design. Bentham assumed visibility would produce compliance. Instead, it often produces performance, the appearance of work, not work itself.

Maybe the most radical act isn't to resist the gaze. It's about actually noticing the watchers. To ask who built the tower, and who benefits from your constant visibility.

The walls aren't just gone. They're inside you now.

If this issue made you see your office differently, share it with a colleague who deserves to know.

Subscribe to Culture Decoded for weekly insights on modern behavior.