{{rh_onboarding_line}}

🌀 The Decode

You set three alarms and clear your schedule. At 10:59 AM, you're hunched over your phone, finger hovering. The page refreshes. "Add to Cart." Click. Loading. Loading. "Sold Out."

The sneakers cost $175. You never touched them. Yet somehow, losing them hurts more than if you'd never wanted them at all.

Welcome to scarcity theatre, the modern ritual where waiting becomes admiration, limitation turns into luxury, and missing out feels like a failure. From Supreme bricks selling for £300 to virtual queues of 70,000 people for a New Balance restock, we've transformed artificial scarcity into a spectator sport.

Why do we desire what we can hardly attain? And who taught us that longing feels better than possession?

Earn Your Certificate in Real Estate Investing from Wharton Online

The Wharton Online + Wall Street Prep Real Estate Investing & Analysis Certificate Program is an immersive 8-week experience that gives you the same training used inside the world’s leading real estate investment firms.

Analyze, underwrite, and evaluate real estate deals through real case studies

Learn directly from industry leaders at firms like Blackstone, KKR, Ares, and more

Earn a certificate from a top business school and join a 5,000+ graduate network

Use code SAVE300 at checkout to save $300 on tuition.

Program starts February 9.

🏺 Field Notes

Long before countdown timers, humans ritualized scarcity to create value.

In traditional Japanese culture, omiyage, the gifts brought back from travels, dates back to ancient Shinto pilgrimages. Pilgrims returning from sacred shrines carried charms as proof of their journey. These objects weren't inherently valuable. They became treasured because they could only be obtained by making the pilgrimage yourself.

The ritual established a sense of 'embedded value,' where an omiyage served as more than a mere object. It was a physical manifestation of giri, proving one’s effort and commitment to a relationship through the lens of social obligation.

Polynesian cultures shared a similar idea. The word tapu, the origin of the term "taboo," denoted sacred items set apart by restrictions. For example, the first fish caught each season couldn't simply be eaten; it was ritually offered, making the rest of the catch more meaningful.

The pattern repeats: restriction fosters reverence. What we can freely possess, we often fail to value.

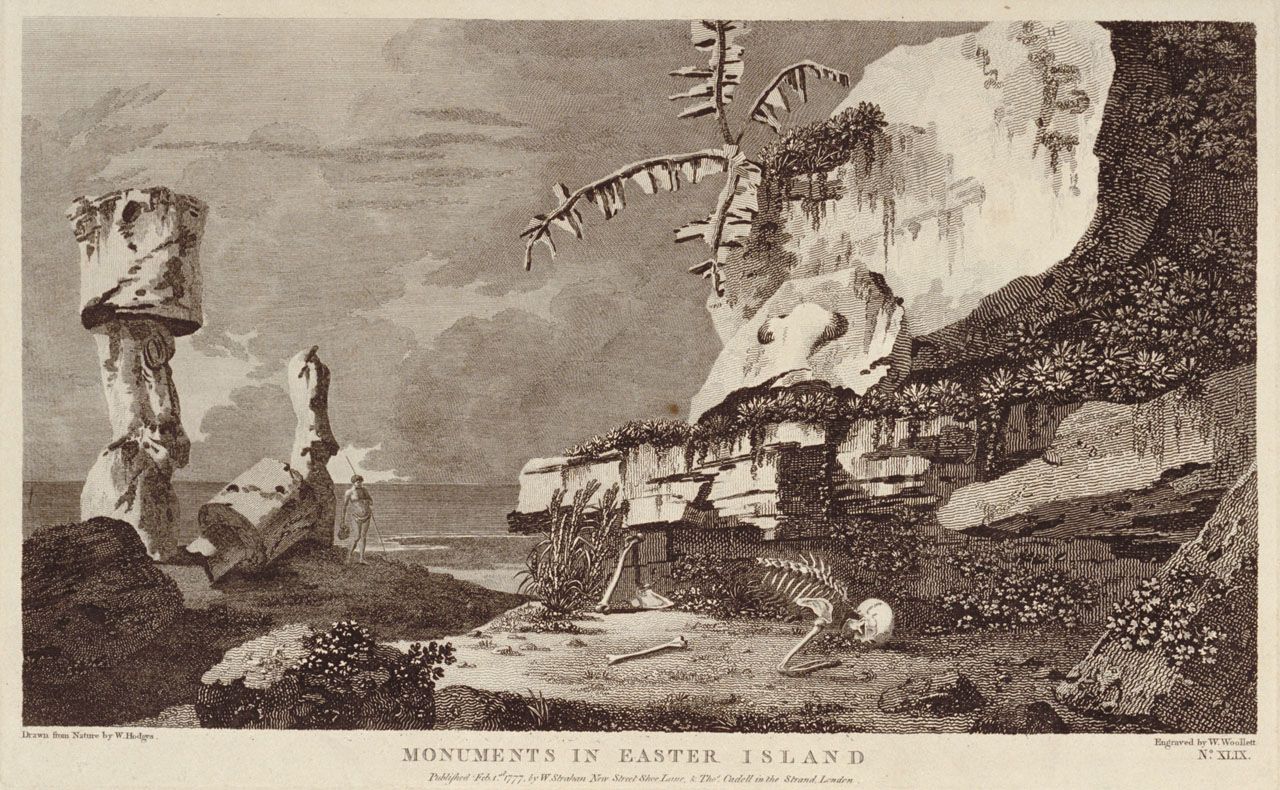

When British explorer James Cook arrived at Rapa Nui in 1774, artist William Hodges documented a society in which chiefs enforced sacred tapu to regulate land and resources. These boundaries were marked by white-topped stone pyramids, which Europeans often mistook for funerary monuments. Credit: © Wellcome Collection

🧩 First Principles

Why do we want something more when others want it too?

Philosopher René Girard dedicated his career to this question. His theory of "mimetic desire" suggests an uncomfortable truth: our desires are not entirely our own. We desire things because we observe others wanting them.

A child neglects a toy for months until another child picks it up. Suddenly, it becomes irresistible. This isn't childish; it's human.

"Desire becomes competitive not because there is necessarily a scarcity of the object," Girard argued, "but because desire is essentially related to the wants of others." We don't pursue objects. We pursue validation to ensure we have the right things.

Scarcity intensifies this mimetic cycle. When 10,000 people want only 500 sneakers, each person's desire increases the pressure on the supply. The queue becomes evidence of worth.

Sociologist Juliet Schor applies this to modern consumption. We no longer compare ourselves to neighbours; we compare ourselves to the aspirational lifestyles on screens. The reference group has expanded infinitely, and so has our sense of what we're "missing."

FOMO isn't irrational. It's the logical endpoint of desire that was never really about the object at all.

🏙️ The Agora

Brands have turned scarcity psychology into an exact science.

In the 2000s, streetwear brand Supreme refined the "drop" model: announce a collection, release items weekly in limited quantities, sell out within minutes. They famously sold branded bricks, crowbars, and toothpaste, none with practical use, all commanding resale prices in the hundreds. The lesson was clear: scarcity drives prices up.

Now the playbook is everywhere. Nike digitized queuing with virtual waiting rooms and Instagram raffles. Booking.com tells you, "15 people are looking at this room right now." Amazon displays the message, "Only 3 left in stock." These aren't informational; they're emotional triggers designed to make inaction feel like loss.

Neuroscience confirms what marketers already knew: scarcity messaging activates our prefrontal cortex's emotional response, encouraging impulsive choices. When we see a countdown timer, our brains respond in a manner similar to that during threat detection.

Research from 2025 revealed that FOMO now acts as the main mediator between social media advertising and purchasing, more influential than the adverts themselves. We don't buy because we're persuaded; we buy because we're afraid of missing out.

The global sneaker market surpasses $131 billion, with forecasts indicating it will reach $215 billion by 2031. Much of that value comes from manufactured scarcity, the strategic limitation that makes abundance appear insufficient.

⚡ Signals

📜 Quote: "Losses loom larger than gains." — Daniel Kahneman, Nobel Prize-winning psychologist

📊 Study: Research published in Nature Human Behaviour confirmed that Kahneman and Tversky's prospect theory replicates across 19 countries: we feel losses roughly twice as intensely as equivalent gains, explaining why "missing out" hurts more than "getting" satisfies.

🎨 Artifact: The Supreme brick, a literal clay brick with a logo, sold for $30, now reselling for $300+. The ultimate proof that scarcity manufactures value independent of utility.

😂 Meme: "Me adding something to my cart that I didn't know existed 5 minutes ago because there's only 2 left in stock."

🤔 Prompt: When was the last time you wanted something more because you might lose the chance to have it? What were you really afraid of losing?

📝 Reader's Agora

What's your worst FOMO purchase? The item you bought wasn't because you needed it, but because you couldn't bear the thought of missing out. Reply and confess, we’re collecting these for a future issue on buyer's remorse. The best stories might appear (anonymously) in an upcoming edition.

🎯 Closing Note

Here's the uncomfortable truth about scarcity theatre: it works because it reveals something genuine about us. We are social beings who compare ourselves to others. We are loss-averse creatures who feel deprivation more sharply than gain. We are meaning-seekers who find significance in restriction.

The drops, queues, and timers aren't causing these tendencies. They're taking advantage of patterns as ancient as pilgrimage and taboo.

The question isn't whether you'll experience FOMO again. You will. The real question is whether you can recognize it for what it is: not proof that you're missing something valuable, but evidence that you're human in a world made to make you feel constantly behind.

Sometimes, the strongest action you can take is to let the timer run out.

If this made you think, share it with someone who needs to hear it. And if you want more cultural decoding each week, make sure you're subscribed.

Subscribe to Culture Decoded for weekly insights on modern behavior.