{{rh_onboarding_line}}

🌀 The Decode

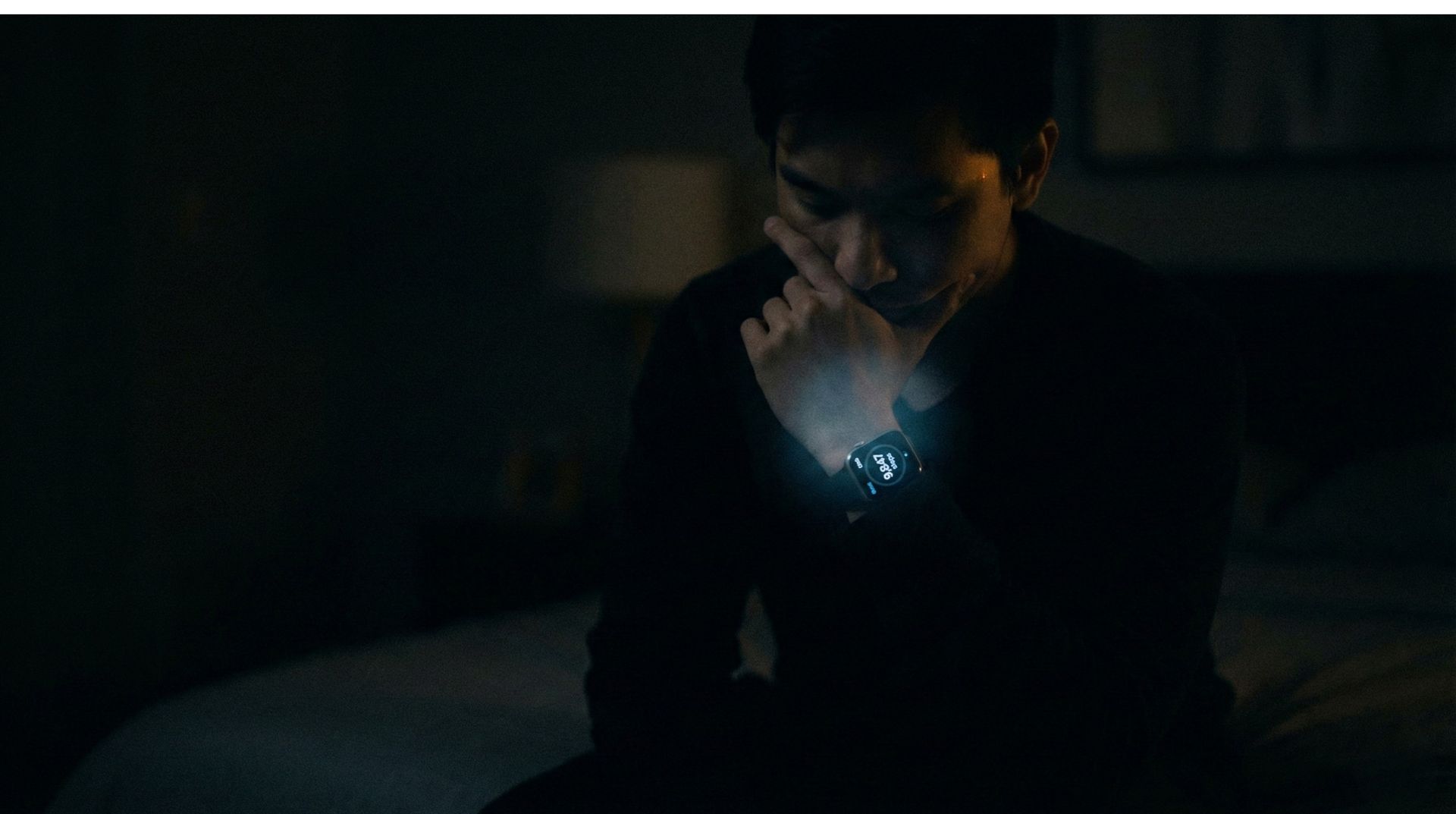

You check your wrist. 7,832 steps. Good, but not quite there. You take the longer way to the bathroom. 7,891. You pace while brushing your teeth. 7,943. Before bed, you walk circles around your bedroom until the watch vibrates its congratulations: 10,000.

Here's the strange part: you didn't feel unhealthy at 9,800 steps. Yet, something about that unmet number made you restless. When did self-knowledge become a matter of arithmetic?

We've been measuring things for forty thousand years. But measuring ourselves through our heartbeats, sleep cycles, and oxygen saturation is a more recent obsession. And it raises an age-old question: Does counting ourselves help us understand who we are? Or does it simply give us another concern?

Smart Investors Don’t Guess. They Read The Daily Upside.

Markets are moving faster than ever — but so is the noise. Between clickbait headlines, empty hot takes, and AI-fueled hype cycles, it’s harder than ever to separate what matters from what doesn’t.

That’s where The Daily Upside comes in. Written by former bankers and veteran journalists, it brings sharp, actionable insights on markets, business, and the economy — the stories that actually move money and shape decisions.

That’s why over 1 million readers, including CFOs, portfolio managers, and executives from Wall Street to Main Street, rely on The Daily Upside to cut through the noise.

No fluff. No filler. Just clarity that helps you stay ahead.

🏺 Field Notes

Humans have been counting for millennia, but the things we count reveal what we value. The Lebombo bone, a baboon fibula with 29 carved notches, discovered in southern Africa, dates to 42,000 years ago. Archaeologists believe it may have tracked lunar cycles, possibly menstrual cycles. Our earliest math wasn't about commerce. It was about time and bodies.

Notched bone from Border Cave, Lebombo Mountains. Source: Adapted from Bruderer (2024). Original photograph by Robert Hart, The McGregor Museum, South Africa. (Image background digitally processed).

However, counting was not universal. Anthropologist Caleb Everett examined the Pirahã people of the Amazon, whose language lacks specific number words, including "one" and "two." Instead, they use terms like "a few." When asked to repeat a line of seven spools, they found it difficult to specify exact numbers beyond three. This does not indicate a lack of intelligence; rather, their culture never required precise digits.

Numbers, it turns out, aren't discovered. They're invented, and we invent them when counting starts to matter. Agriculture demanded it. Trade required it. And now, wellness culture insists on it. The question is whether our bodies needed the counting, or whether the counting created new needs.

🧩 First Principles

"Know thyself." The words were carved above the Temple of Apollo at Delphi in ancient Greece, and Socrates made them the foundation of his philosophy. But here's what's worth noting: Socrates wasn't talking about data.

In Plato’s dialogues, Socratic self-knowledge meant examining one's beliefs, testing one's assumptions through conversation, and uncovering what one thinks one knows but does not. In the Apology, Socrates declares that "the unexamined life is not worth living." The emphasis was on dialogue rather than measurement. The soul, Socrates argued, was the self worth knowing. And you couldn't weigh it on a scale.

The philosopher Michel Foucault revisited this in the context of modernity. He wrote about technologies of the self, practices people use to transform themselves in accordance with certain ideals. Prayer journals, confession booths, and exercise regimens, each era invents new techniques for self-improvement. Foucault saw that these techniques always reflect the values of their time.

Today's self-technology centres on the dashboard. We've moved from self-examination to measurement. However, if Socrates was right that self-knowledge involves examining our beliefs, then our trackers might be addressing a different question, revealing what we do rather than who we are.

🏙️ The Agora

The global fitness tracker market was valued at over $60 billion in 2024 and is projected to nearly triple by 2030. According to the Pew Research Centre, roughly one in five Americans regularly uses a smartwatch or fitness tracker. We are, quite literally, a measured species now.

Yet the magic number most of us chase, 10,000 daily steps, wasn't born from science. It came from a 1965 Japanese marketing campaign. A company called Yamasa Clock launched a pedometer named the Manpo-kei, which translates to "10,000 steps meter." The number was catchy, not clinical. Subsequent research has found that health benefits plateau around 7,500 steps, but the myth persists because round numbers appear to be real goals.

The psychological effects are complex. A 2019 study found that most wearable users felt empowered, but those with certain personality traits experienced guilt, anxiety, and self-consciousness, especially when unable to wear their device. Researchers have even coined a term for the self-surveillance these devices enable: the heautopticon, a play on Foucault's panopticon, but turned inward. We've become our own watchers.

⚡ Signals

📜 Quote: "Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted." — William Bruce Cameron, Informal Sociology (1963). Often misattributed to Einstein, this line originated with a sociologist grappling with the limits of measurement.

📊 Study: The study published by the Journal of the American Heart Association found that among 83 people using wearables to monitor heart conditions, one in five experienced "intense anxiety" with some describing themselves as "prisoners of the numbers."

🎨 Artifact: The Manpo-kei pedometer (1965), a Japanese device whose name became a global health commandment. Its marketing slogan invented a metric we still chase sixty years later.

😂 Meme: Your smartwatch: "Great job! You walked 10,000 steps today!" You, who paced your apartment at 11 PM to hit the goal:

🤔 Prompt: What would you learn about yourself if your tracker broke for a week and you had to feel instead of count?

📝 Reader's Agora

I'm curious: Has a metric ever made you feel worse about something you used to feel fine about? A sleep score that convinced you that you're tired? A heart rate that made you anxious? Reply and tell us, we want to hear how the numbers changed your relationship with your body.

🎯 Closing Note

Here's the paradox: We track ourselves to gain control, but the tracking can become its own kind of captivity. The Delphic oracle never asked how many steps you took. Socrates didn't count his heartbeats. Self-knowledge, in the ancient sense, was about examining your beliefs, not your biometrics.

Numbers can illuminate. But they can also distract. The real question isn't what your watch says about your body. It's what you believe about your life, and whether you've stopped to examine it lately.

If this made you think, share it with someone who needs to hear it. And if you want more cultural decoding each week, make sure you're subscribed.

Subscribe to Culture Decoded for weekly insights on modern behavior.